Plants

Plants: Mighty Producers

Plants and animals have adapted to their environments over millions of years, to become experts in their domains. They have adapted to incredibly varied conditions, from tundras to tropics in partnership with other species around them. For example, the American Honey Suckle, on PEI coincides with its flowering time exactly with the arrival of the Ruby-throated hummingbird in the summer, so that it can get pollinated, as the hummingbird gathers nectar from plant to plant.

Learning the Language of Plants

We have so much to learn from our plant friends, all we have to do is take a closer look. Plants are so different from one another, but we often lump them together as one.

It is best to start with the absolute basics. Plants do so much for us, we know they are important-- they produce all of our food, and oxygen and are therefore the basis of all life. Having a basic understanding of the fundamental characteristics of plants helps us to appreciate them for all of the services they provide for not only us humans, but the entire ecosystem. As we move into looking at more detailed characteristics of types of plants, we can start to identify them, which helps us know which plants are safe to eat, which are good to use for shelter, for medicinal purposes and more.

Learning Language: Plants

Natural History of Plants

The first plants were mosses, which covered the earth about 500 million years ago in the Cambrian period and paved the way for all plant life to follow. All plants, including huge trees and small forest shrubs, evolved from algae, which do not have leaves or the ability to store water. The evolution of plants follows the adaptation for this need to store energy from the sun, and water. Early plants developed leaf-like structures to give them a bigger surface area to capture sunlight, and root-like structures to hold water. Vascular plants (plants that move nutrients and water within) began to emerge in the form of ferns with spores (a method of asexual reproduction) and then gymnosperms (plants with naked seeds spread via wind), leading the way to early conifers (trees with needles).

Early plants existed only near water but would later slowly adapt to be able to spread further and further away from wetland areas, as they developed roots. Seeds evolved as a way to spread the genetics (inherited characteristics) of a plant. Seeds have a whole host of incredible adaptations, such as being light, with fuzzy tips to travel by wind (think of a dandelion seed), and shooting systems so that plants can launch seeds farther and farther.

Angiosperms (plants that produce flowers and fruit) evolved later and offered flowers, facilitating reproduction through pollen. Along with the emergence of angiosperms came more ways of protecting and attracting others to the seed, as well as larger leaves, with vein structures for stability, and more surface area for capturing sunlight.

The emergence of angiosperms coincides with the arrival of insects, as plants discovered if they made their seeds more attractive, by adding colourful flowers, they could attract insects to come pollinate and fertilize their seeds. The explosion of plants of different shapes and sizes, non-woody and woody was then made possible. As this complex community of plants grew, they modified the environment, produced leaf litter that turned into soil, and it became easier and easier for life to exist on Earth.

Fruit and berries evolved with the emergence of birds and mammals, as they were highly nutritious and calorie-dense sources of food. Animals helped the spread of these plants because they carried seeds and pooped them out far away, allowing a species to establish itself.

Seeds: Other adaptations came from challenges plants had to overcome to protect their seeds from animals that would not do a good job of carrying their seed, or eat them too fast. Plants might protect their precious seeds by making thorns, carrying seeds too high up for certain mammals, or producing leaves that make some birds sick or taste bad. Plants have evolved to spread their seed as efficiently as possible, so their seed is designed accordingly, to get the most yield for the least amount of energy.

Ecology

All life depends on plants and the processes they expertly perform. Considering plant ecology requires both big-picture thinking and attention to small details. Broadly, plants sustain life, and by taking a closer look, we can see how they adapt to a huge variety of environments with incredibly detailed characteristics that coincide with animals and the geological and physical processes in that environment.

Plants are specially adapted with incredible techniques to fit into their environment. Consider the Bayberry shrub. Its leaves are waxy and stiffer than those of forest-loving shrubs. Its leaves have evolved to have a protective barrier so that it can live near the coast, and not become damaged by the salty spray, or harsh winds that we feel near the ocean.

Plants create habitats for animals; trees with big woody trunks and large reaching branches provide habitats for birds, insects, and mammals- not to mention a host of various lichens and mosses. When they die, their standing dead trunk, called a snag is a perfect home to host a family of raccoons, owls, birds, like nuthatches, and countless insects. When it finally does fall, it becomes yet another habitat for other important animals like salamanders. At each step of its life, it is a host for an entire community of plant and animal species.

Produces oxygen: Plants take carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and in return give us the ability to breathe oxygen. We would not be able to exist without plants!

Nutrient cycles: Plants are autotrophs, meaning they make their food themselves. They take in carbon as a ‘food’ source, in the form of carbon dioxide, turning it into sugars and storing it in their roots. This is essential, as too much carbon in the atmosphere is harmful to the rest of life on Earth. Plants also gather food from the sun, through photosynthesis, storing energy from the sun in their cells and passing it off to other organisms as it dies or gets eaten. Another essential nutrient is nitrogen. Although plants all require different levels of nutrients, a great many plants are nitrogen-fixing plants, meaning they take in nitrogen from the atmosphere, and store it in their roots thanks to rhizobium bacteria in their root systems. These plants include legumes like peas, beans, and alder trees. This nitrogen fixing creates a natural fertilizer for other plants around them. Another key nutrient that plants process is hydrogen, which is passed through trees and other plants in the form of water, as it is taken up through the plant's structure, and released through its leaves as part of the hydrogen cycle.

Food source for animals: Many animals are herbivores, and plants provide the basis for their entire diet. Tree and shrub buds, needles, roots, nectar, berries, seeds, nuts, and leaves are all food sources for animals. For carnivorous animals, plants are still important. Plant energy is simply transferred to them in the form of meat. A fox would not be able to survive without the young trees and shrubbery it takes to sustain a snowshoe hare. Humans are animals and need plants of course too! More than half the world's population relies on plants like corn and rice as our main source of nutrition, and we all need vegetables and fruit to be healthy. One of the main reasons humans have been able to sustain such large populations is due to our ability to harvest plants in such quantities through farming plants, to create everything from grains for making breads and cereals to grapes for making wine and juice.

Fuel: The death of ancient plants and animals millions of years ago created fossils, which we can use as fossil fuels such as oil, coal, and gas, which are solely responsible for industrial society. This organic material that has been preserved by sedimentation, and other geological processes is a finite resource under the earth's surface.

Diversity in species and age: The more plants there are in an area the more biodiverse (diversity of life forms) that area will be. Because plants are the producers, their existence in an area increases the likelihood of other animals in that area. Having many different plant species in an area means many different animals might be indicted to come and live there. A healthy habitat, such as a forest, will have trees, and shrubs of varied ages, as well as species including many at the decomposing stage. This means there will be a continued seed source and healthy soil for seeds to germinate. The more diverse an area is, in age and species the more resilient it is. This means it is better able to deal with problems that come up, like disease, or destruction.

Key Characteristics

Nutrition: Plants can photosynthesize, meaning they convert sunlight into energy. Plants have evolved to adapt to their conditions, therefore some plants require different amounts of light and nutrients in the soil. However, some plant species do not photosynthesize. A good indicator of a plant that does photosynthesize is the colour green: chlorophyll is green in plants and is a by-product of this photosynthesis. Some plants, instead of photosynthesizing live on other plants, and use the host as a means of nutrition. Others obtain their food from dead organic matter, and some, (like the pitcher plant we have on PEI) are even carnivorous, luring insects and consuming them. Fungi are a separate group, and not in the plant family. They do not photosynthesize or make their food, instead, they feed on their host.

Structure:

Plants have cellulose in their cell walls (made from sugars) making them stiff and strong and giving structural support. Humans cannot fully digest cellulose, although we do need it for fibre, but many animals can. It also is the main ingredient in paper and many other similar products. Cellulose is the principal component of wood.

Woody plants: We can describe trees and shrubs as woody plants. They are adapted to grow strong and tall, reaching over ferns and other herbaceous plants to capture more light and attract birds in the forest.

Lignin: Woody Plants have lignin in their cell walls. Lignin makes the cells stiff, enabling woody plants to grow larger than non-woody plants.

Leaves: Behave like solar panels for the plant, capturing sun on their surface. Leaves can also sense temperature, and air quality and are a large indicator of the health of a plant.

Needles: The way that conifers preserve water and survive through the winter, is because of their needles. They are the leaves of coniferous trees, and stay on the tree all year long, giving conifers the name 'evergreen' (there are some however, that lose their needles, for example, the Eastern larch, which we have here on PEI).

Roots: Enable a plant to store their energy, access water from the soil, and filter water through to the ground for a sustainable water source. They also provide stability for a plant, allowing it to grow tall, without toppling over. Roots help prevent soil erosion, are a food source for animals, and also provide hiding spots for rodents' food stores for the winter.

Vascular: This descriptive word tells us if a plant can take up water through its stem/trunk (vascular like trees, flowers), or does not take up water through a stem (non-vascular like mosses, algae lichens).

Life Cycle of Plants

Seeds: A seed is an incredible package that includes all the information a plant needs to live, and reproduce. One single seed can become an entire forest if left long enough! Seeds are designed with unique adaptations formed in collaboration with their environment to assist in the spreading of a plant's genetic makeup (traits from their parents). Plants might have flowers, fruit or nuts to carry their seed (angiosperms), like an acorn on an oak tree, or have exposed seeds (gymnosperms) like pinecones. Some seeds may also be in the form of spores like we see on ferns, which do not require fertilization (fusion of male/female parts to reproduce).

Reproduction: Pollination thanks to animals like insects and birds, helps fertilization of a seed. Plants will make seeds designed for the most efficient reproduction: some may have protective laters to help store that seed over the winter and germinate in the spring, some are designed to be so light they can travel by wind, and some have evolved to have juicy fruit, like berries, so it will be eaten, carried, and pooped out later. A plant will also have other structural characteristics to facilitate reproduction, such as flowers, for attracting pollinators, and thorns for keeping others out.

Germination: Refers to the point when a seed sprouts, or comes to life! Different plants require different conditions to germinate. Some, like the Red Oak Acorn, need a cold winter to crack open and sprout in the spring. And some, even need forest fire conditions so the seed can open up.

Life: Plants may be perennials meaning they have a dormant stage, but come back to life every year. They might be annuals, meaning they start from a seed and die when their life cycle has been completed (often producing another seed at the end of its life). Plants throughout their life will be incredible habitats for animals, produce oxygen, and filter nutrients through them, allowing life on earth to continue. As leaves, needles, and small branches fall they contribute to a healthy forest floor, making it a good bed for more plants to grow.

Death: Plants are valuable at all stages, even after they die. A plant that offers dead, dried-out leaves or stalks provides great material for nest-making for a bird! A tree that is dead, but still standing is a home for a squirrel or bird nest, and flowers that die off fall onto the soil and its nutrients get recycled for the next round of plants. Deadwood is a critical part of a healthy forest in PEI, because it creates habitats and healthy soils.

Decay: Soil is made up largely of decomposing organic material (plants that are breaking down). Leaf litter (fallen leaves and needles), rotten logs (fallen trees), old roots, sticks and stalks, all make up the soil. Decaying plant material is food for invertebrates, like worms and their structures provide habitats and protection from predators for amphibians. Decaying plants have a huge amount of nutrients stored from their lives as living plants, and that energy filters into the soil, spreading further and further out, and taken up by new plants.

Learning language

A learning language is simply a way of describing and identifying features and patterns that we see. If you see a beautiful tree on the side of the road and would like to know more, you could use language like this to describe what you see: “It was a tall tree and had compound leaves, growing in an opposite pattern and bark with distinct ridges”. This way of describing something focuses on curiosity and learning, and on recognizing the patterns in living things, instead of the focus being on knowing the plant species' name. We cannot expect to recognize plants without a system for identifying them- there's just too much to look at!

Describing Woody Plants: Trees and Shrubs

-

What is a Tree? The largest living organism on earth. Typically, it grows with a single stem. Our largest tree on PEI is the white pine which is recorded to have grown over 2m in diameter and over 36m tall, with roots that can stretch for 2-3X the tree's height! Learn more about trees on PEI.

-

What is a shrub? Multi-stemmed and low-growing woody plants. Usually no taller than 4-6m. Examples of PEI are Chokeberry, beaked hazelnut, Wild raisin, and Dogwood. Learn more about shrubs on PEI.

-

Bud: Are on all trees and shrubs, and is where the leaves and branches will come from. They are a small growth or protuberance along the stem of a branch or at its terminal end. A great time to look at buds is early spring before they open up with leaves.

Types of trees: coniferous and deciduous

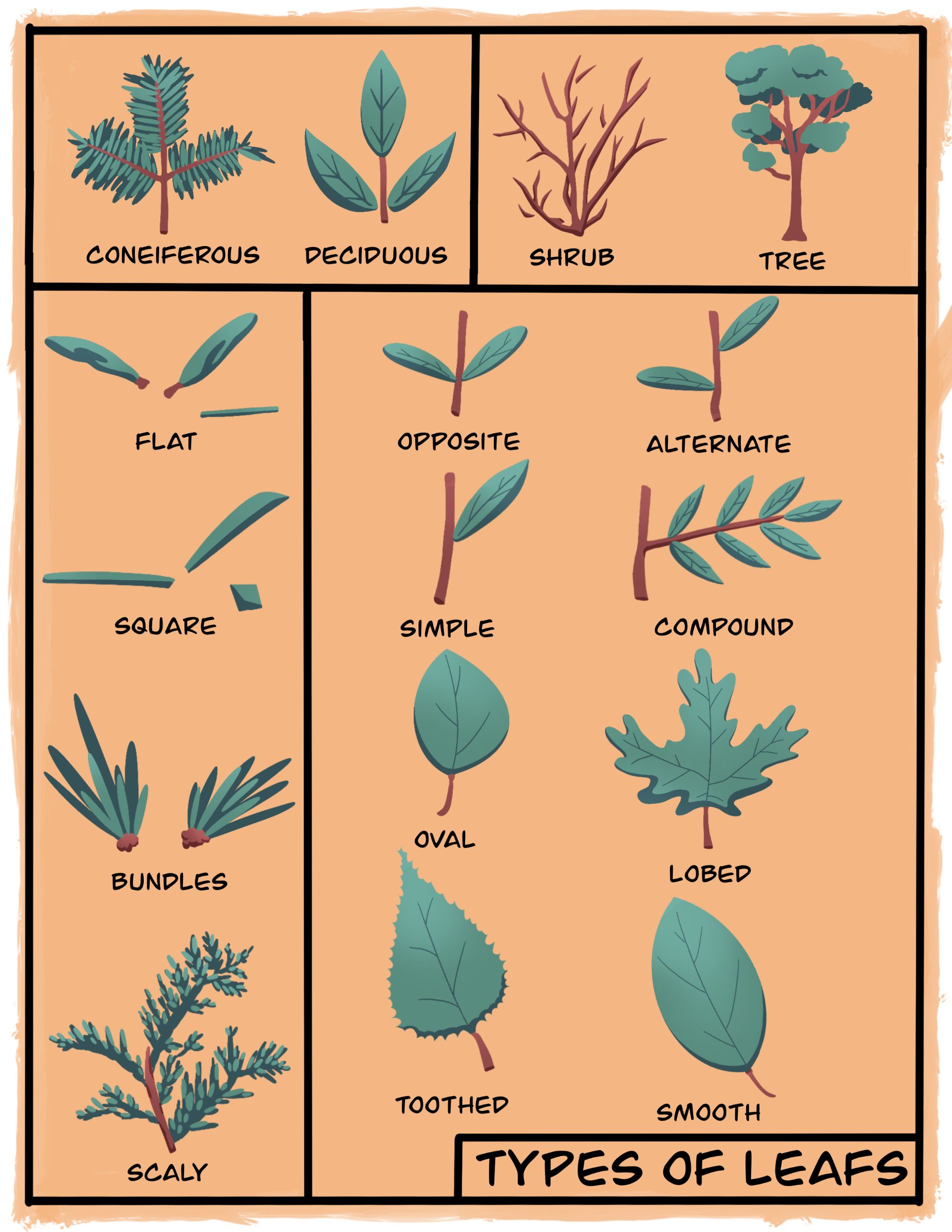

Coniferous - The word coniferous is easy to remember if we link it to the word cone. Conifers, like pine and spruce trees, will have cones to carry their seeds. Coniferous trees or shrubs are often called evergreen because they have needles that remain on the tree year-round. Conifer needles can be flat (like hemlock, or balsam fir), square (like spruce), grow in bundles (like pine, or larch), or be scaly (like cedar). There are only 9 species of conifer native to PEI.

You can describe conifers by their needles:

-

Shape: notice how the individual needle feels in your fingers if you roll it between them. It is flat, or square? Or are they Scaly and flat?

-

Length: Are the needles long like a pine, or short like a spruce?

-

Groups: notice the branch, are the needles spread out along the branch, or clustered in bundles?

-

Bundles: If a conifer has bundles of needles, it can give you clues about the species (ex: White pine has bundles of 5, Red pine has bundles of 2).

Deciduous - Trees or shrubs that lose their leaves in cooler months to preserve energy. They have leaves, which can be arranged in different growing patterns and have different shapes.

Types of leaf arrangements in deciduous trees and shrubs can be:

-

Growing patterns can be opposite - leaves that grow opposite one another or alternate - leaves grow alternately along the stem.

-

Leaf structure can be simple - where a single leaf is produced from a single bud (like a maple leaf). There is always a bud at the base of the leaf. Or Compound, which is a leaf composed of multiple leaflets (like an Ash or Sumac). The bud will be found at the base of the leaf and not at the base of each leaflet (small-looking leaves on one compound leaf).

-

The shape can be described as oval (like a birch leaf); there are many different leaf shapes, linear, oblong, obovate, and cordate, however oval covers a host of leaf shapes and is easy for children to remember or Lobed which are leaves that have an irregular shape (like an oak leaf).

-

The edges can be toothed, where the margin or edge of the leaf has a jagged edge like a saw, or be Smooth when you run your finger along it, is not pointed but is smooth.

See the diagram for leaf composition